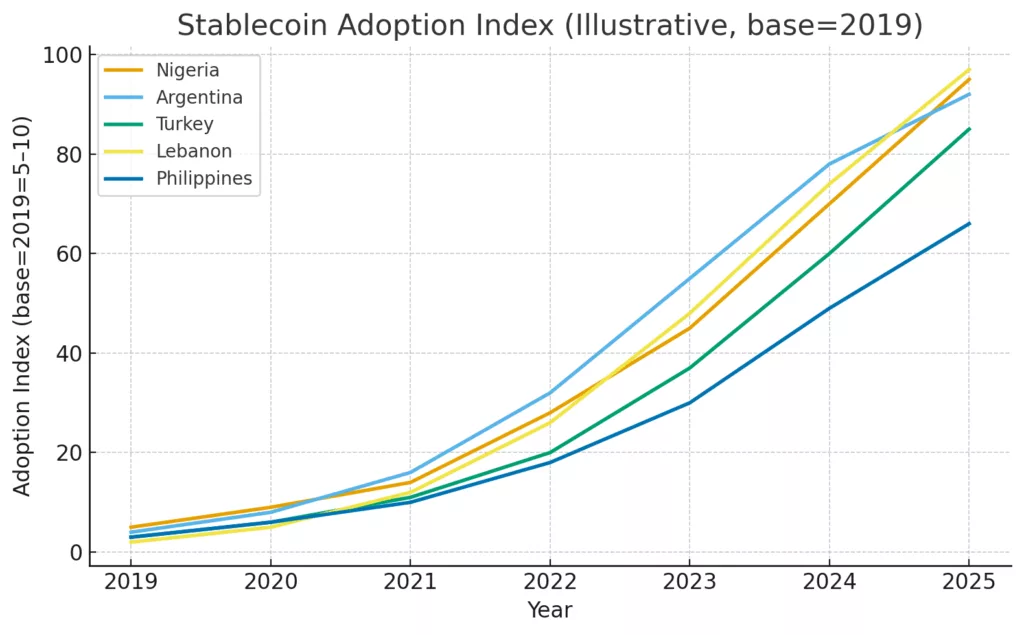

Developing nations have frequently served as the testing ground for financial innovations. From mobile money in Kenya to dollarization in certain regions of Latin America, communities with volatile currencies often embrace new types of money more rapidly than their developed counterparts. Stablecoins represent the newest competitor in this cycle, being digital tokens linked to the U.S. dollar or other fiat currencies that offer efficiency, accessibility, and protection against inflation. Beneath the positive outlook, there exists a more profound structural risk: the increasing use of stablecoins poses a threat to local banking systems, undermines monetary authorities, and centralizes financial power with a limited number of global issuers.

Why stablecoins flourish in emerging economies

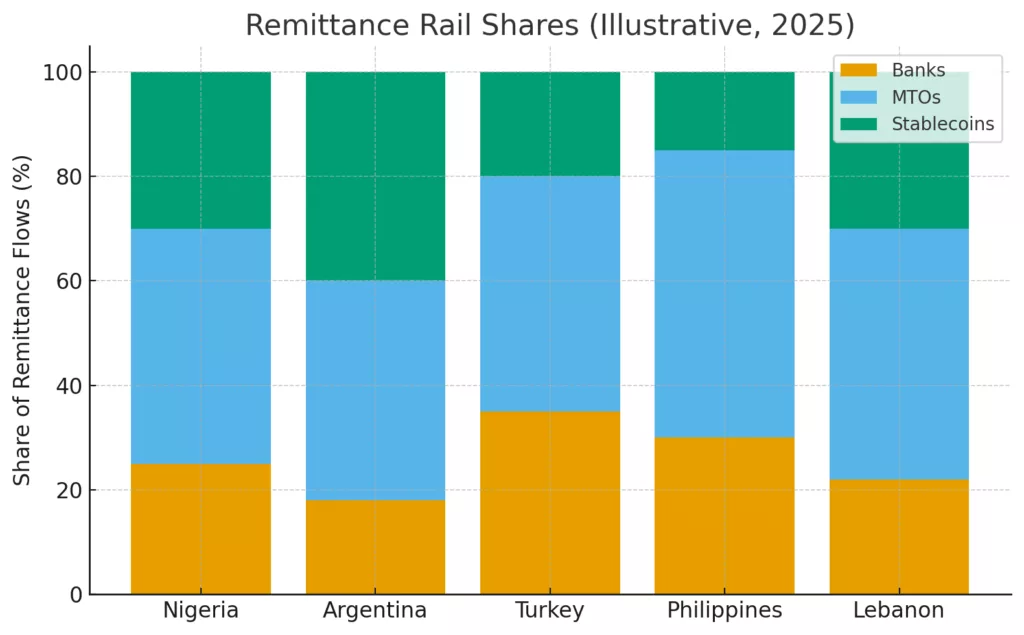

The drivers of stablecoin adoption are clear. In countries plagued by inflation and currency depreciation, stablecoins like USDT and USDC offer instant access to dollar stability. Remittances, often lifelines for families in places like Lebanon, Argentina, and Nigeria, flow faster and cheaper when denominated in stablecoins rather than through banking corridors riddled with fees. For small merchants and freelancers paid in crypto, the appeal is undeniable: a globally accepted, easily transferable form of money without bureaucratic friction.

However, these advantages reflect local shortcomings. When people resort to stablecoins, it indicates not only innovation but also a distrust in local currencies and banking systems.

The banking disinter mediation problem

Conventional banks depend on deposits to finance loans. When households and businesses transfer their savings from local bank accounts to stablecoins, the domestic deposit base declines. This results in a dual liquidity squeeze: banks possess fewer resources to provide loans, and central banks lack clarity on the money supply.

In economies that use the dollar, this decline is even more pronounced. Stablecoins efficiently “bring in” U.S. monetary policy to vulnerable markets, circumventing local interest rates or reserve regulations. The result is a weakening of national banking systems, rendering them progressively less significant in financial intermediation.

The shadow dollarization effect

Stablecoins enhance a type of shadow dollarization that varies from the use of physical currency. In contrast to dollar bills that move through informal channels, stablecoins exist on blockchains outside of government control. They facilitate extensive, swift international transactions that regulators cannot detect until systemic stresses arise.

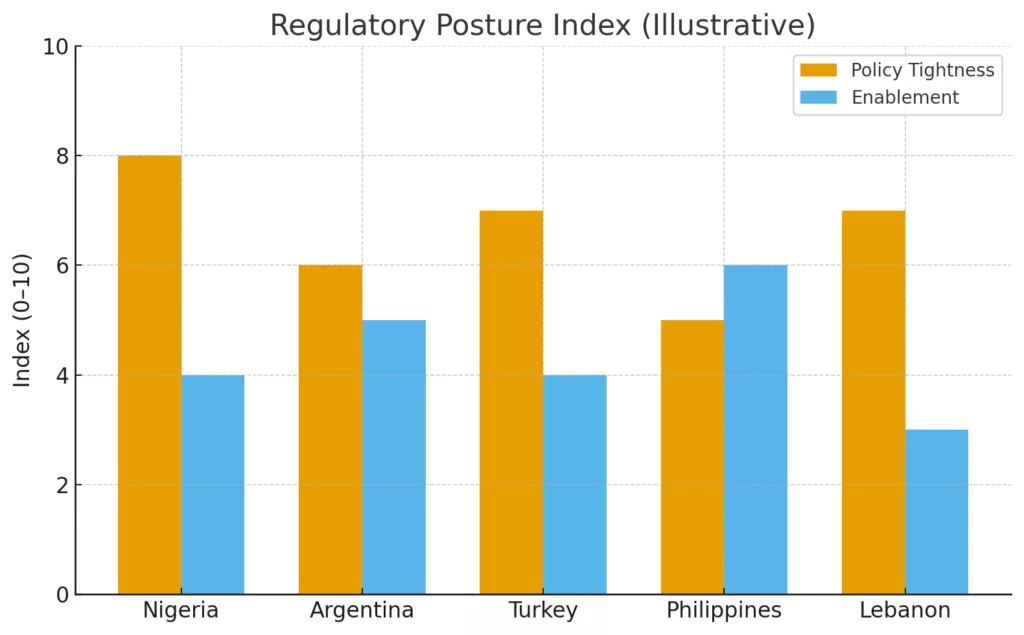

This weakens capital controls for governments in emerging markets and complicates the management of macroeconomic factors. The tools that central banks rely on to stabilize economies such as exchange rate interventions, tightening monetary policy, or selective lending are rendered less effective when individuals turn to blockchain-based currencies.

The systemic risk concentration

The irony of adopting stablecoins is that the rhetoric of decentralization conceals centralization in reality. Several private issuers, frequently located overseas, manage most of the circulating supply. Tether’s prevalence in developing markets implies that local financial systems are indirectly vulnerable to the solvency, governance, and reserve transparency of a single entity.

A liquidity shock, such as a widespread redemption incident or a regulatory halt, could affect nations distant from the issuer’s home country. In reality, whole economies might be vulnerable to the operational risk posed by a single stablecoin provider.

Potential responses by regulators and banks

Governments are becoming aware of these hazards. Certain central banks are considering central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) as protective options. Others are imposing stricter regulations on crypto exchanges and money transfer services. However, strict prohibitions frequently have the opposite effect, driving usage underground and weakening trust even more.

For local banks, the challenge is fundamental. To compete with stablecoins, it might be necessary to incorporate blockchain infrastructure, provide digital wallets, or even convert deposits into tokens. Those who do not adjust face obsolescence in a world where investors no longer regard them as secure refuges.

Between promise and peril

Stablecoins are not fundamentally harmful. For people in uncertain economies, they offer genuine support and connectivity to international markets. However, on a larger scale, they reveal structural weaknesses: impairing banking systems, eroding monetary sovereignty, and concentrating systemic risk beyond national boundaries.

The narrative of stablecoin acceptance in developing nations represents a contradiction that empowers individuals but weakens institutions. The outcome of a more open, efficient financial system or a crisis will rely on how swiftly banks and regulators adjust their roles in an era driven by blockchain technology.