Blockchains, in their current form, rely on the premise that specific mathematical problems are virtually impossible for computers to solve. Bitcoin, Ethereum, and the majority of other blockchains depend significantly on elliptic-curve cryptography, specifically the ECDSA method, to protect user wallets and verify transactions. Ethereum depends on BLS signatures for the agreement of validators. These algorithms are secure against classical computers since resolving the foundational discrete logarithm problem would require an immense amount of time.

Quantum computing alters the entire scenario. Shor’s algorithm, executed on a sufficiently strong quantum computer, can resolve both discrete logarithms and integer factorization in polynomial time. This immediately compromises ECDSA, EdDSA, and BLS signatures. In other terms, the specific system ensuring that solely you can utilize your coins becomes exposed once quantum machines surpass a particular limit.

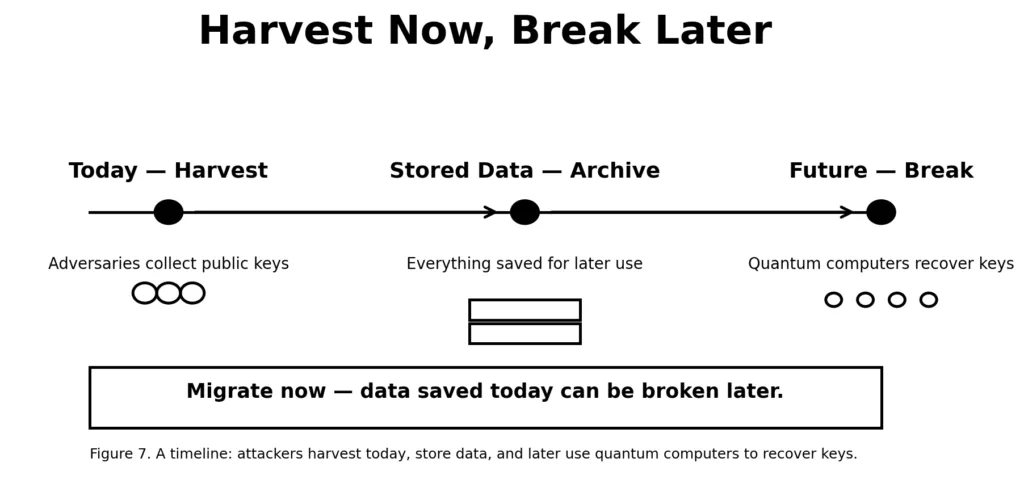

A more nuanced danger exists, referred to as “harvest now, decrypt later.” Today, adversaries have the ability to capture blockchain data, retaining all transactions and exposed public keys. As quantum computers advance, they will be able to decipher those keys after the fact and deplete funds that remain obtainable from vulnerable addresses. This risk is particularly critical for blockchains due to the immutable and public nature of the ledger, which forms a lasting record of targets for potential future quantum attackers.

Grover’s algorithm, a different quantum method, accelerates brute-force assaults on symmetric encryption, yet this issue can be resolved easily by increasing key lengths. Shor’s algorithm poses an existential threat. Consequently, the enduring existence of blockchains depends on the integration of novel cryptographic primitives that maintain security in a post-quantum era.

The good news standards are here

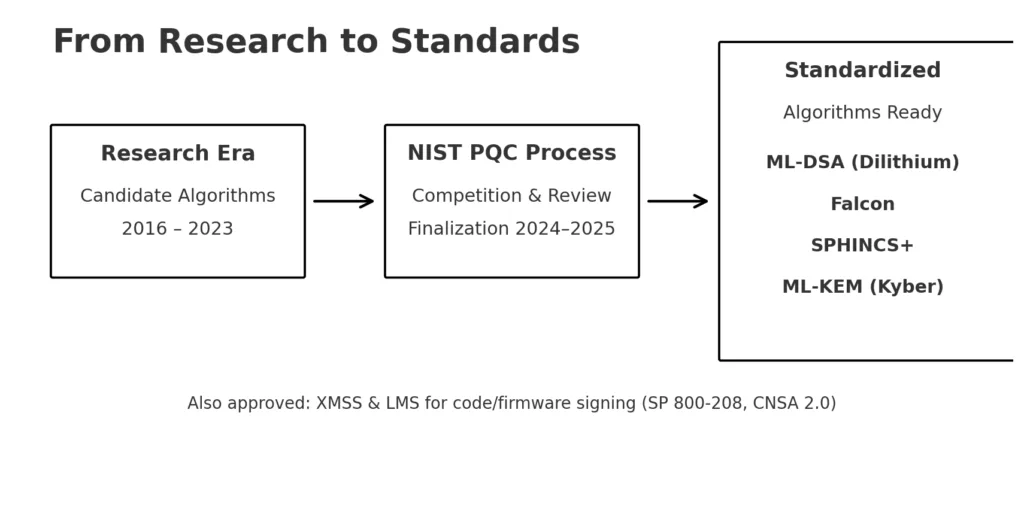

For many years, the conversation surrounding post-quantum was merely theoretical. All acknowledged that quantum computers would ultimately pose a risk to blockchains, yet without standardized options, discussions remained confined to scholarly articles. That has evolved. NIST has now completed its initial set of quantum-resistant cryptographic standards following a thorough multi-year competition. These standards provide blockchain developers with tangible components for implementation.

The signature schemes are the most crucial of them all. CRYSTALS-Dilithium, currently referred to as ML-DSA, provides robust security, moderate signature lengths, and rapid verification. Falcon, a different lattice-based approach, generates smaller signatures and is effective for verification, but necessitates more careful implementation. SPHINCS+, a signature based on hashing, is stateless and conservative; however, its bigger signatures render it less practical for daily blockchain applications.

In addition to signatures, CRYSTALS-Kyber, now recognized as ML-KEM, has emerged as the standard option for key encapsulation, facilitating secure key exchange among parties. Although blockchains seldom utilize key exchange directly, cross-chain bridges, off-chain channels, and specific wallet protocols can gain advantages from it.

Hash-based methods have also been improved. NIST Special Publication 800-208 has already sanctioned XMSS and LMS for code signing, and the U.S. NSA’s revised CNSA 2.0 suite now mandates these algorithms for the protection of federal software and firmware. In the context of blockchains, this is particularly significant for node clients, validator software, and consensus-essential code; if governments are requiring these components, it indicates a strong sign of preparedness.

This moment is significant for the blockchain sector. Engineers no longer need to inquire if proposed schemes will pass standardization. They may begin incorporating ML-DSA, Falcon, and SPHINCS+ directly into wallets and consensus applications, confident that these algorithms are endorsed by international standards and will receive support for many years. In summary, the post-quantum roadmap has evolved from a research subject to a tangible engineering resource.

Algorithm families in plain english

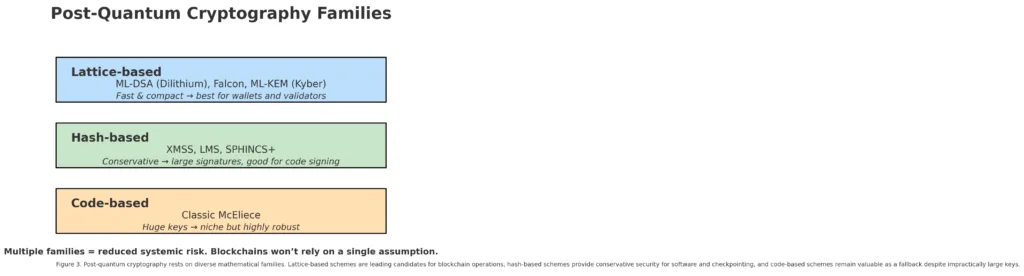

The variety of post-quantum algorithms can seem daunting. Every method has its unique mathematical basis, distinct signature sizes, and varying performance compromises. However, in the context of blockchains, the scenario becomes clearer when you consider the function of each category.

The primary and most significant family is lattice-based cryptography. ML-DSA, based on Dilithium, is the NIST standard for digital signatures. It generates keys and signatures of medium size and verifies swiftly ideally suited for blockchain accounts and validators. Falcon, a different lattice-based scheme, generates smaller signatures and is even more space-efficient on-chain, yet it poses greater challenges for safe implementation. Both depend on structured lattice problems that are deemed quantum-resistant.

The following are the signatures based on hashes. XMSS and LMS have been approved in NIST’s SP 800-208, while SPHINCS+ successfully completed the NIST process as a stateless alternative. These approaches are cautious, relying on the robustness of cryptographic hash functions instead of novel algebraic assumptions. The downside is the signature size: SPHINCS+ signatures can reach several kilobytes, leading to on-chain bloat. However, for applications such as client software signing, firmware integrity, or checkpoint anchoring, they are unrivaled in terms of simplicity and dependability.

Ultimately, there exist the code-based methods, like Classic McEliece. These depend on codes that correct errors. They are viewed as very secure yet experience significantly large public key sizes, occasionally reaching hundreds of kilobytes. This renders them unsuitable for wallets or validator signatures, yet they still exist in the standards collection for specialized applications.

This classification is important for blockchain developers. It indicates that the primary toolkit is already varied: lattice signatures for routine accounts and validators, hash-based signatures for anchoring and software, and code-based methods as a cautious backup. The shift relies on multiple robust assumptions it spans different mathematical families, lowering systemic risk.

What this means for major chains

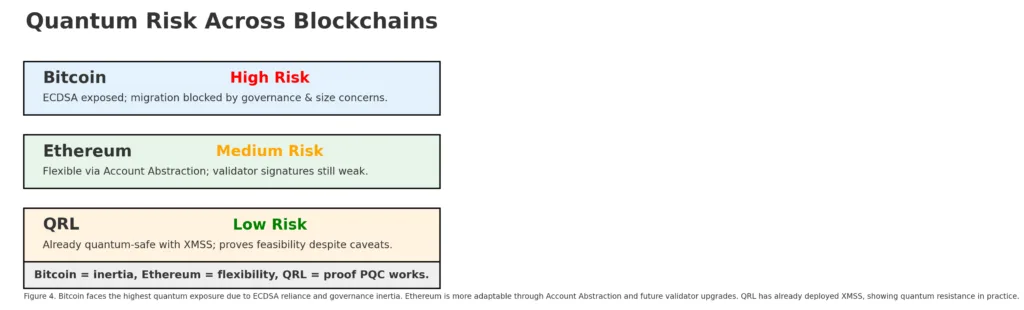

The shift to quantum-safe cryptography will impact each blockchain differently. Every ecosystem depends on its specific cryptographic primitives and possesses various upgrade trajectories. Comprehending these distinctions is crucial for identifying which networks are more vulnerable and which possess natural migration benefits.

Bitcoin is the most cautious blockchain regarding updates. It depends solely on ECDSA with secp256k1 for user accounts. Each time a Bitcoin user utilizes coins, their public key is disclosed. In a post-quantum landscape, this implies that anyone who has ever conducted a transaction might be at risk if their assets stay unspent at that location. Taproot has enabled more adaptable spending conditions, facilitating the use of hybrid quantum-safe scripts or even the direct implementation of hash-based signatures such as SPHINCS+ or XMSS. The challenge is as much cultural as it is technical: persuading a traditional community to embrace larger signatures and scripts that could inflate the chain will be challenging. Migration in this context is feasible, but it necessitates extended transition phases, significant motivators, and meticulous design for compatibility.

The transition to quantum-safe cryptography will affect every blockchain in unique ways. Each ecosystem relies on its particular cryptographic primitives and has different paths for upgrades. Understanding these differences is essential for determining which networks are more susceptible and which have inherent migration advantages.

Bitcoin is the blockchain that approaches updates with the most caution. It relies exclusively on ECDSA with secp256k1 for user accounts. Every time a Bitcoin user spends coins, their public key is revealed. In a post-quantum future, this means that anyone who has completed a transaction could be vulnerable if their assets remain untouched at that site. Taproot has allowed for more flexible spending conditions, promoting the use of hybrid quantum-resistant scripts or even the straightforward application of hash-based signatures like SPHINCS+ or XMSS. The difficulty is both cultural and technical: convincing a traditional community to adopt larger signatures and scripts that may increase the chain will be tough. In this context, migration is possible, but it requires prolonged transition periods, strong incentives, and careful planning for compatibility.

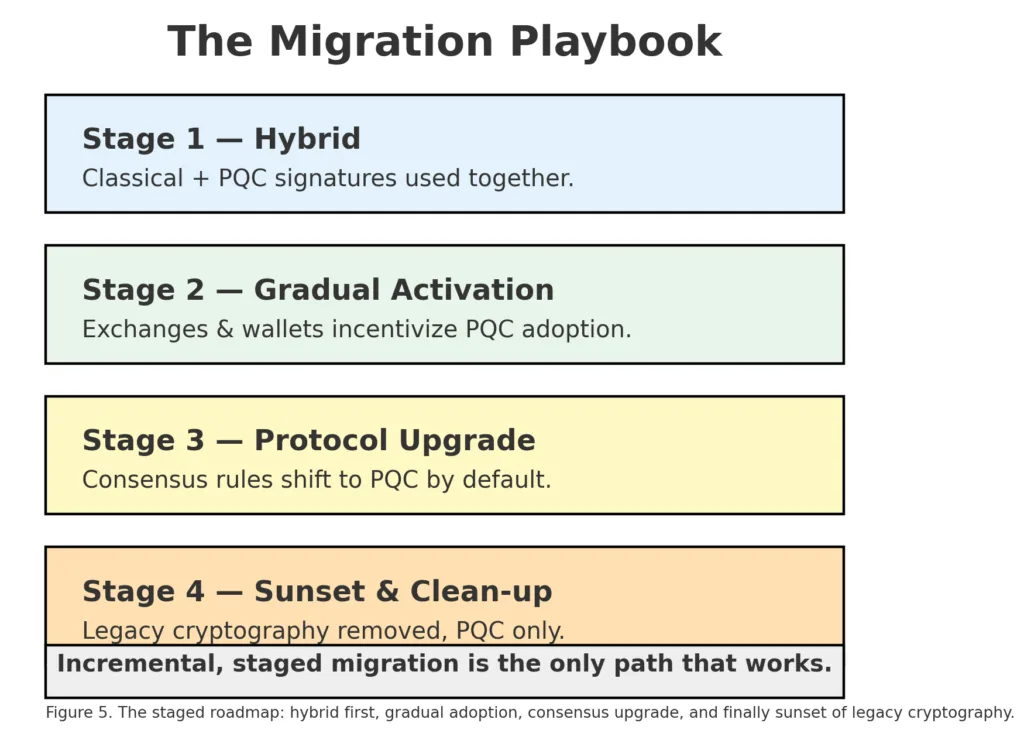

The migration playbook

Discussing quantum risk is simple; implementing a migration is the challenging aspect. For blockchains, transitioning to quantum-safe cryptography involves balancing three aspects: technical viability, financial expense, and community agreement. The effective playbook is gradual, phased, and ensures backward compatibility.

Stage 1 — Hybrid cryptography

The initial phase involves adding quantum-safe signatures in addition to traditional ones. Rather than completely replacing ECDSA or BLS, wallets and validators can utilize both for signing. This indicates that current infrastructure continues to operate, while future-oriented users receive quantum assurance. Taproot on Bitcoin and account abstraction on Ethereum now enable hybrid scripts and wallets.

Stage 2 — Gradual activation

When hybrid schemes become accessible, developers can motivate users to transition slowly. Exchanges, custodians, and payment processors may necessitate quantum-safe addresses for incoming deposits. Protocols may provide fee reductions for PQC transactions. This gradual shift prevents disrupting the chain while guiding the ecosystem toward safety.

Stage 3 — Protocol upgrade

Ultimately, traditional schemes must be phased out at the consensus level. For Bitcoin, this would entail new soft forks that eliminate raw ECDSA scripts. For Ethereum, signatures at the validator level must change from BLS. This phase is both politically and technically demanding, yet inevitable.

Stage 4 — Sunset and clean-up

The last step involves addressing legacy risks: transferring unspent outputs on Bitcoin, enhancing smart contracts that incorporate traditional verification, and refreshing node software to disallow insecure elements. This guarantees that years into the future, no hidden vulnerabilities exist for a quantum attacker to take advantage of.

This step-by-step approach balances immediacy with feasibility. Should developers try to implement PQC right away, chains would split. If they delay indefinitely, they invite disaster. Hybrid-to-sunset signifies the migration path that achieves equilibrium.

The economic and governance layer

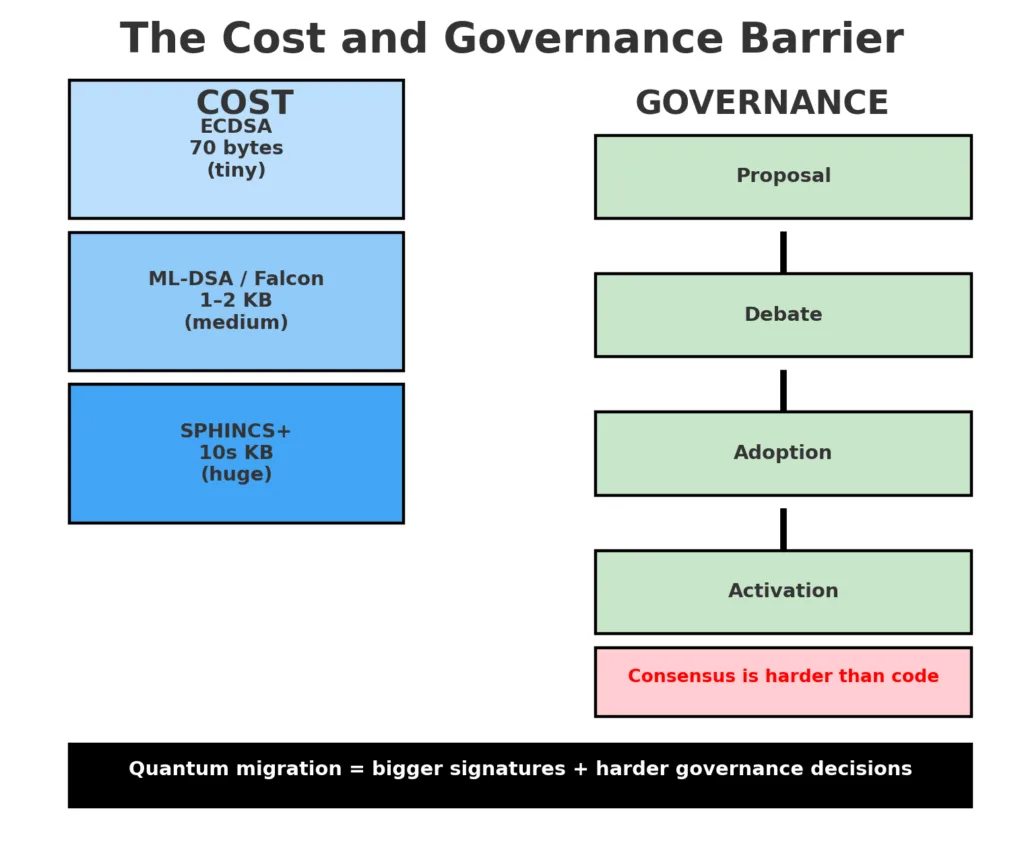

Although the cryptography is prepared and engineers can create hybrid rollouts, the reality is that blockchains do not evolve in isolation. They improve in political economies, where every byte recorded on-chain incurs a cost and every alteration in the protocol demands widespread agreement.

Economic costs.

Quantum-safe signatures are larger. A Bitcoin transaction utilizing ECDSA is approximately 70 bytes for each signature. A SPHINCS+ signature may range up to several tens of kilobytes. Even the more efficient lattice-based signatures, such as ML-DSA and Falcon, remain larger than ECDSA or BLS. This results in increased block space usage for each transaction, decreased throughput, and possibly elevated fees. In Ethereum, the efficiency of validator aggregation diminishes with larger signatures, posing a direct risk to block times and scalability. In a system where space incurs costs, every byte is significant, and PQC is naturally costlier.

Governance hurdles.

Blockchains operate based on broad agreement and financial motivations. The history of Bitcoin demonstrates how controversial even small adjustments to block size can be. Ethereum offers greater flexibility, yet still necessitates consensus among clients, developers, and validators. Implementing PQC will involve not only technical accuracy but also persuading communities to invest in safety ahead of a potential quantum attack. This demands planning and collaboration in environments that frequently incentivize immediate benefits.

The timing dilemma.

If chains delay migration until large-scale quantum computers are available, it might be too late for a safe transition, as attackers may have already collected vulnerable data. However, if they move too soon, they risk incurring substantial economic costs for a threat that might not occur for many years. The governance layer must consequently strike a balance: establishing migration paths now, even if activation occurs at a later time.

Ultimately, the debate on quantum migration will be determined within the economic and governance framework. The cryptography is prepared, but without a commitment to incur expenses and manage upgrades, chains face the danger of stagnation against the certainty of quantum advancements.

The “harvest now, break later” economy

The most overlooked quantum risk isn’t the one that emerges with the first functional quantum computer, but the one occurring quietly at this moment. Blockchain transactions are transparent, and the majority of traditional cryptography (ECDSA, RSA, BLS) is based on the premise that it is practically impossible to derive the private key from a public signature. Quantum computing shifts that belief, but importantly: data captured today will remain at risk for many years ahead.

Harvesting today.

Attackers can extract data from blockchains now, recording every transaction and signature they encounter. This is currently occurring on a large scale research studies and intelligence revelations verify extensive archiving of encrypted messages and financial information. For blockchains, this implies that every ECDSA signature on Bitcoin and each BLS signature on Ethereum validators could be accumulated, anticipating the moment when Shor’s algorithm becomes viable.

Breaking later.

When a capable quantum computer is finally developed, this archive turns into a treasure trove. Attackers may recover private keys from previous signatures and create fraudulent transactions. They wouldn’t even have to hack active wallets; they could deplete long-dormant addresses, such as Satoshi’s original coins, old exchange wallets, or neglected multisig wallets. The belief that “if it was secure upon signing, it remains secure indefinitely” fails.

The urgency.

This dynamic of harvesting now and addressing issues later strengthens the rationale for immediate PQC migration compared to the vague notion of “quantum someday.” Chains cannot afford to wait until quantum computers are available. By that time, the harm will have already been ingrained. Blockchains can only eliminate this risky time gap by migrating signatures before they become exposed.

In other words: the quantum attack has already started it just hasn’t been executed yet.

Choosing algorithms that fit blockchains

Selecting a post-quantum signature scheme is not a one-size-fits-all decision. Different blockchains, with their distinct transaction patterns and architectural priorities, will gravitate toward different standards. Among the NIST finalists, three stand out: ML-DSA (Dilithium), Falcon, and SPHINCS+.

ML-DSA (Dilithium) has emerged as the leading candidate for general-purpose use. Its verification is fast, its design is straightforward to implement, and it avoids reliance on fragile assumptions or exotic arithmetic. While its signatures are larger than ECDSA or BLS, they remain manageable for wallets and validators. For blockchains seeking the strongest balance between performance, simplicity, and deployability, Dilithium offers a solid “default” path forward.

Falcon appeals to projects that want compact signatures. Its outputs can be less than half the size of Dilithium’s, saving valuable block space. But this comes at the cost of implementation complexity. Falcon relies on floating-point arithmetic and Gaussian sampling, both of which have historically been sources of subtle bugs. A chain that standardizes on Falcon must invest heavily in auditing, formal verification, and rigorous testing to avoid catastrophic edge-case failures.

SPHINCS+, by contrast, takes a conservative, hash-based approach. Its signatures are far larger often 15 KB or more and verification is slower than lattice-based options. But its security foundations are extremely well understood. This makes SPHINCS+ attractive for tasks like software release signing, firmware updates, or anchoring checkpoints on-chain. It is less suited to high-frequency transactions but excels where robustness outweighs efficiency.

A crucial caveat is that none of these PQC schemes natively support signature aggregation. Protocols that rely on compact multi-signatures, like Ethereum’s BLS-based validator sets, will need new engineering solutions to replace or approximate aggregation. For now, blockchains face trade-offs between size, speed, and security assumptions with Dilithium as the pragmatic choice for most.

Road ahead and conclusion

The transition to quantum-safe cryptography is not just a technical challenge it is a governance, economic, and social one. Upgrading blockchains will involve consensus changes, wallet updates, coordination among developers, and communication with millions of end users. Some projects may pursue hybrid approaches to preserve backward compatibility, while others may opt for more aggressive cutovers once PQC implementations mature.

The greatest danger lies not in overestimating quantum timelines, but in underestimating the risk of inaction. Every classical signature added to a blockchain today could be harvested and broken decades from now. That makes the problem urgent: migration must begin before quantum computers are powerful, not after.

Blockchains were designed to outlast governments, corporations, and even generations of hardware. To fulfill that mission, they must now prove they can outlast the quantum threat. By embracing PQC, the industry demonstrates that decentralization is not just about removing trust from intermediaries, but about securing trust for centuries to come. The next decade will determine whether blockchains stand as quantum-resistant pillars of digital trust or relics of a pre-quantum era.