MEV as a trillion-dollar shadow economy

The emergence of MEV has subtly altered blockchains into systems that extract value in ways strikingly reminiscent of conventional tax frameworks.In the absence of laws, politicians, or regulatory bodies, blockchains have established automated processes that drain value from users the instant they engage with the network.MEV has evolved into a clandestine economy where each transaction is subject to taxation, not by state authorities but by algorithms vying for transaction priority.

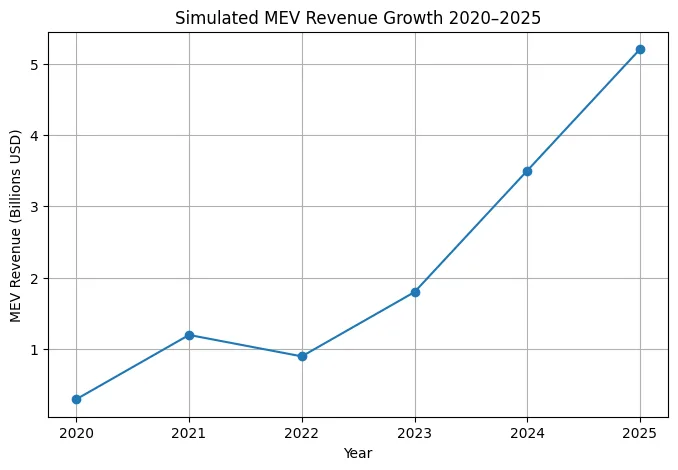

This unseen tax is realized through practices such as sandwiching, arbitrage, liquidation races, and gas auctions, forming an economic layer that the majority of users remain unaware of contributing to.By the year 2025, MEV is anticipated to surpass one trillion dollars cumulatively, thereby positioning it as one of the most significant unintended economic systems ever devised.The pertinent question has shifted from whether MEV is present to whether blockchains can endure without recognizing it as a fundamental force influencing liquidity, pricing, and token valuations.

Sandwich attacks function like value-added tax

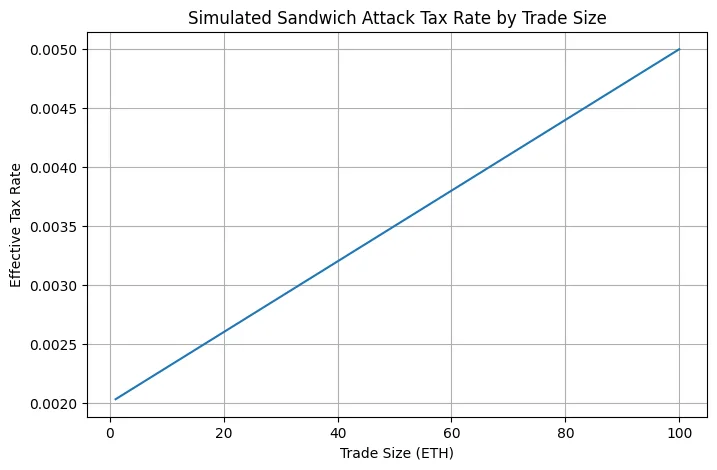

A sandwich attack takes place when a bot detects a user’s trade and carries out transactions both prior to and following it. The bot ensures profit by manipulating the price, which leads to the user unintentionally paying a higher price. This mechanism operates similarly to VAT: every purchase carries a markup that benefits an intermediary rather than the seller. However, in contrast to VAT, the user remains unaware of the tax rate and does not consent to its payment; the blockchain enforces this through mempool transparency and automated execution. As decentralized exchanges experience increased volume, sandwich attacks create a continuous, unavoidable tax on retail traders, transforming MEV into a behavioral tax that penalizes urgency and rewards bots with comprehensive information. In fast chains like Solana and Tron, the frequency of these attacks resembles real-time micro-taxation.

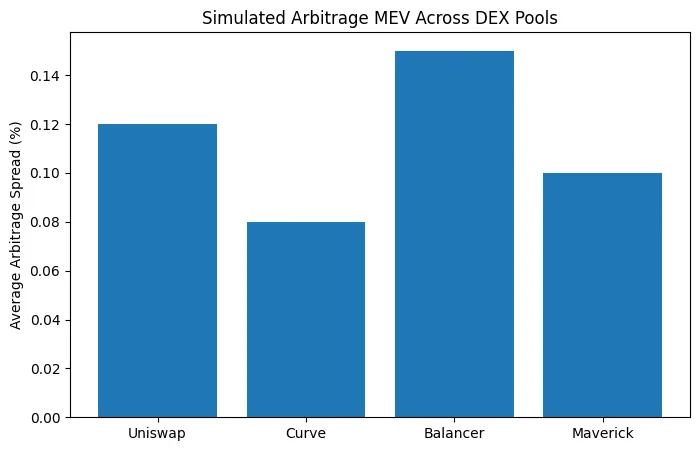

Arbitrage MEV behaves like import–export taxes

Cross-DEX arbitrage functions by balancing price discrepancies among liquidity pools.Automated bots operate similarly to customs agents: each time assets transition from one market to another, a fee is imposed. This process is akin to import-export taxation.MEV arbitrage imposes a toll whenever liquidity shifts between decentralized exchanges (DEXs), establishing an economic barrier around substantial pools such as Curve, Uniswap v3, and Maverick.

Chains characterized by fragmented liquidity face considerably higher arbitrage taxes, resulting in increased costs for users attempting to perform cross-market transactions.As the quantity of rollups rises, this tax becomes more pronounced due to further fragmentation of liquidity, which in turn generates additional arbitrage opportunities and escalates the costs incurred by traders.Consequently, the arbitrage economy evolves into a continuous tax loop, propelled by inefficiency and latency.

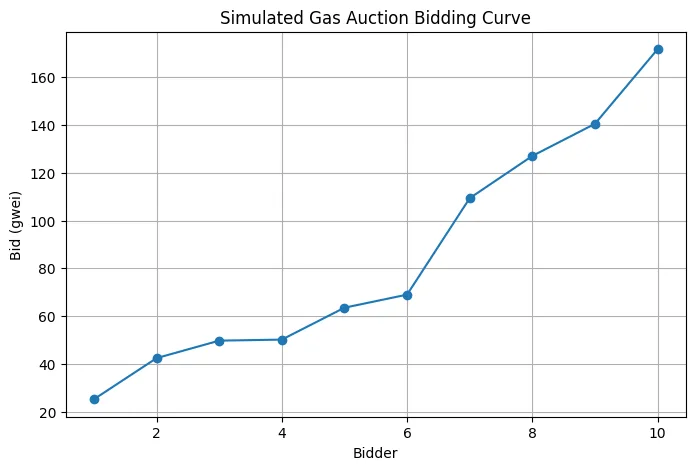

Gas auctions are competitive tax bidding

When numerous bots strive to seize the same opportunity, they engage in what seems to be an auction for block space. This situation mirrors competitive bidding for the privilege of collecting taxes. Rather than governments auctioning carbon credits or toll rights, MEV searchers offer gas fees to secure access to the most lucrative transactions. The highest bidder essentially compensates the network as a tax collector, while users indirectly bear the costs through increased gas volatility. In 2024, the emergence of builder markets, PBS (proposer-builder separation), and private routing intensified this auction dynamic, resulting in a sophisticated market where builders extract tax revenue while searchers function as competitive contractors. Gas serves as the bidding currency within this automated tax system.

MEV mitigation becomes a form of economic policy

As MEV increasingly takes on characteristics similar to taxation, mitigation mechanisms evolve into the blockchain’s version of tax reform.Changes to protocols, including encrypted mempools, MEV-burn, threshold decryption, and SUAVE, introduce new economic policies that modify the dynamics of value extraction.

For example, MEV-burn on Ethereum redirects MEV profits to ETH holders by burning gas, effectively acting as a redistribution mechanism.In a similar vein, frameworks for private order flow and intents seek to minimize parasitic tax extraction by safeguarding retail flows.

Currently, each blockchain selects its own tax regime: Solana prioritizes speed over protection, Ethereum explores redistribution, and Cosmos provides application-specific tax structures.These choices influence liquidity migration, validator incentives, and the overall trajectory of chain economies.

Influence on token valuations in 2025–2026

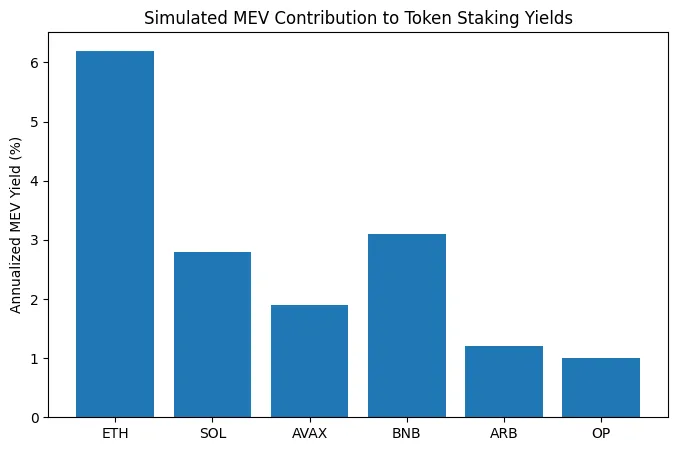

By the years 2025 to 2026, MEV economics is anticipated to emerge as a significant driver for the repricing of L1 and L2 tokens.Chains that transform MEV into yield for stakers, such as Ethereum with PBS, EigenLayer AVS, and MEV-burn, will have their valuations linked to their capacity to monetize order flow.

Networks that experience uncontrolled MEV leakage will face value extraction without a corresponding benefit to the native token.Liquidity providers are expected to increasingly shift towards “low-tax” ecosystems where MEV protection is most robust.

Institutional capital will regard MEV as a quantifiable cash flow, akin to payment-for-order-flow revenues in traditional markets.The chains that effectively manage or capitalize on MEV will excel, and token valuations will hinge on the sustainability of their MEV tax model.

Source:Generated with Python,chains with stronger MEV capture and redistribution deliver higher staking yields, positioning ETH as the dominant beneficiary in the MEV-driven valuation model.