Bitcoin mining has evolved beyond the traditional model where profit came solely from the difference between block rewards and a fixed electricity rate. After the 2024 halving, the enterprise currently occupies the intersection of three markets that persistently fluctuate in opposition to one another: energy markets that assess the cost of electrons based on location, time, and congestion; compute markets that transform joules into hashes utilizing rapidly evolving ASICs and thermal management; and capital markets that fund operations, measure risk, and progressively divide mining revenue into tradable assets. “Mining Economics 2.0” serves as the platform for that convergence. It views the miner not merely as a price-taker, but as a multi-asset player overseeing basis risk among power, hashrate, and Bitcoin.

Miners exploit energy price differences by pursuing the least expensive and highly variable megawatts: on-site renewables, curtailed solar and wind, wasted or flared gas, run-of-river hydro during transitional seasons, and utility initiatives that compensate for reducing load during grid pressure. On the computing front, the focus has transitioned from outright performance to performance per watt. Discrepancies in efficiency between contemporary and older ASICs establish an internal hierarchy, while immersion processes, under-volting, and power-limiting firmware transform thermal conditions into financial tools. On the financial aspect, the toolkit now encompasses hashrate forwards and swaps, difficulty-related structures, power hedges and capacity entitlements, machine pre-payments and vendor funding, along with layered overlays utilizing BTC options and basis trades.

The outcome is a company that operates as a vertically integrated commodity manufacturer. Revenue consists of the BTC price, transaction fees, and the opposite of network difficulty, while costs include power tariffs, congestion, curtailment penalties, leases, cooling, maintenance, and capital depreciation. Value generation arises from overseeing the foundation among those layers through data, agreements, and operational adaptability. While “Mining 1.0” focused on achieving the lowest average cents-per-kWh, “Mining 2.0” emphasizes flexibility: movable or interruptible loads, varied power sources, adaptable fleets, and a risk management strategy that is proactively hedged instead of passively accepted.

This function serves as a useful guide for that change. We will review traditional economics, then explore contemporary energy arbitrage, the microstructure of the ASIC market, and the updated revenue stack. We will examine the derivative tools currently accessible to miners, create a cohesive hedging guide, detail treasury and funding strategies, identify regulatory and accounting obstacles, and conclude with a future KPI framework that distinguishes sustainable franchises from commodity price-takers.

Mining Economics 1.0 what changed and why it matters

During the initial ten years of the industry, mining operated as a fairly straightforward enterprise. Revenue can be illustrated on a napkin as the result of three factors: the dollar value of bitcoin, the block reward along with transaction fees, and a miner’s share of the overall network hashrate. Difficulty recalibrated biweekly to maintain consistent block intervals, mitigating shocks over time, yet the basic operational guideline was straightforward: transform electricity into hashes as inexpensively as feasible, prioritize uptime, and allow scale to handle the remainder. The main limitation was obtaining affordable electricity; the entity that achieved the lowest cost per kilowatt-hour and maintained operational machinery triumphed in the profitability competition.

Hardware cycles bolstered this straightforwardness. Every successive ASIC generation brought a distinct improvement in joules-per-terahash, and the profit window favored early purchasers who could implement their systems before the curve stabilized. Depreciation was foreseeable since machines adhered to an S-curve: rapid profitability at introduction, a plateau as rivals converged, and a movement toward breakeven as efficiency spread across fleets. The journey to expansion included securing equity in bull markets, collateralizing machines or self-mined BTC for term loans, developing megawatt blocks close to industrial power sources, and opting for a pool payout strategy that weighed variance against costs. The majority of operators utilized PPS, FPPS, or PPS+ to transform stochastic block discovery into reliable cash flow, exchanging a minor fee for consistency.

Electricity acquisition aligned with that consistency. Numerous miners entered into fixed-price retail or slightly indexed wholesale agreements, or positioned themselves behind industrial meters with limited exposure to locational marginal prices. Volumetric charges were predominant; demand charges, congestion, and real-time imbalances were less significant. The grid regarded miners similarly to any other consistent industrial load and seldom involved them for ancillary services. The economic factors came down to the difference between “hashprice” and total electricity costs, with operational expenses primarily influenced by energy and some hosting, cooling, and maintenance costs. Hedging, when it occurred, involved scheduled BTC sales at regular intervals and sporadic forward sales of equipment.

That world started to unravel long before the latest halving. Efficiency improvements from consecutive ASICs drove the industry to a merit order among fleets: the latest rigs offered higher bids for power as they generated more hashes per joule, while older rigs only operated when electricity costs were low enough. Difficulty rises shortened the period miners had to recuperate capex. Fee markets, previously an afterthought, began to act like an actual commodity, experiencing sporadic spikes that could increase the transaction revenue portion by two or three times for days before normalizing. Energy markets, altered by the swift integration of renewables, shifted from a single price structure to a fluctuating curve featuring negative prices in oversupply, high premiums in scarcity, and significant value within elasticity

The halving finalized the transition. Due to the subsidy being reduced by half, breakeven curves tilted upward and removed the marginal machine from the network at every specified tariff. The previous approach of purchasing long-term fixed-price electricity and operating at full capacity no longer maximized earnings. Miners utilizing identical hardware but varying power strategies experienced differing results: those able to reduce consumption during high prices and increase during low periods obtained significant gross margins. Simultaneously, capital markets figured out how to assess the risk associated with digital infrastructure. Equipment suppliers provided prepayment and revenue-sharing models; lenders became stricter on collateral requirements; exchanges and OTC desks introduced hashrate-indexed forwards and swaps; and power desks started quoting shaped blocks, capacity rights, and participation in ancillary services for large flexible demands.

Two other modifications restructured motivations. Initially, pools and firmware advanced. Detailed telemetry, automatic tuning, and power limitation converted thermal management into an adjustable financial gauge. A facility might aim for a dollars-per-megawatt-hour limit and allow firmware to pursue an ideal joules-per-terahash value in both ambient and immersion settings. Secondly, grids uncovered miners. System operators understood that a rapid, interruptible compute load acts like a battery with immediate response, and they were prepared to compensate for that behavior via demand response, non-spin ancillary services, and customized curtailment credits. What seemed to be idle time in Mining 1.0 turned into a source of income in Mining 2.0.

All of this renders the legacy framework inadequate. Considering electricity as a uniform average cost, viewing machines as fixed efficiency points, and regarding BTC as the sole hedgeable variable misses significant value and leaves excessive risk unaccounted for. The contemporary miner needs to manage basis relationships: the difference between real-time and contract power, the difference between hashprice and difficulty, and the difference between BTC spot and derivatives. Mobility options across locations, flexibility across time, and adaptability across firmware configurations are now valued like an asset rather than just a convenience. The companies that will thrive in the upcoming cycle are those that restructure the P&L into a portfolio of measurable, contractible, and dynamically hedged exposures instead of a singular wager on BTC and a utility cost.

Energy arbitrage turning electrons into optionality

The key revision in Mining Economics 2.0 is that power is transformed from a single line item into a collection of shapes, nodes, and contingencies. In the traditional model, a miner secured a fixed rate and optimised operational time. In the contemporary framework, the miner acts as a price-sensitive industrial load that purchases various exposures including day-ahead blocks, real-time float, curtailed renewable, behind-the-meter surplus, and compensated interruptions, combining them into the most cost-efficient megawatt for hashing. That transition depends on grasping how electricity is truly priced, not at the retail meter but in wholesale markets that settle every five minutes and differ by location.

At the heart is locational marginal pricing. Electricity does not have a uniform price throughout a grid; instead, it possesses a nodal price that indicates generation expenses, transmission congestion, and losses. Two locations fifteen miles apart may have varying hourly costs and different chances of negative pricing when wind or solar exceed local demand. A miner who views cents-per-kilowatt-hour as fixed loses cash whenever congestion escalates or scarcity pricing activates; a miner who analyzes nodal distribution gains flexibility by remaining mobile, interruptible, or both. This is why site selection has favored areas with detailed real-time markets; ERCOT’s five-minute dispatch is a prime illustration, along with interconnections that offer flexible curtailment rights, transforming volatility into a rebate instead of a penalty.

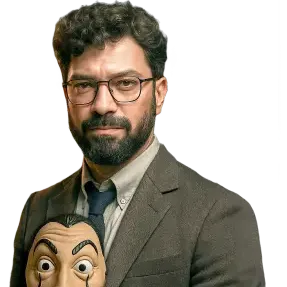

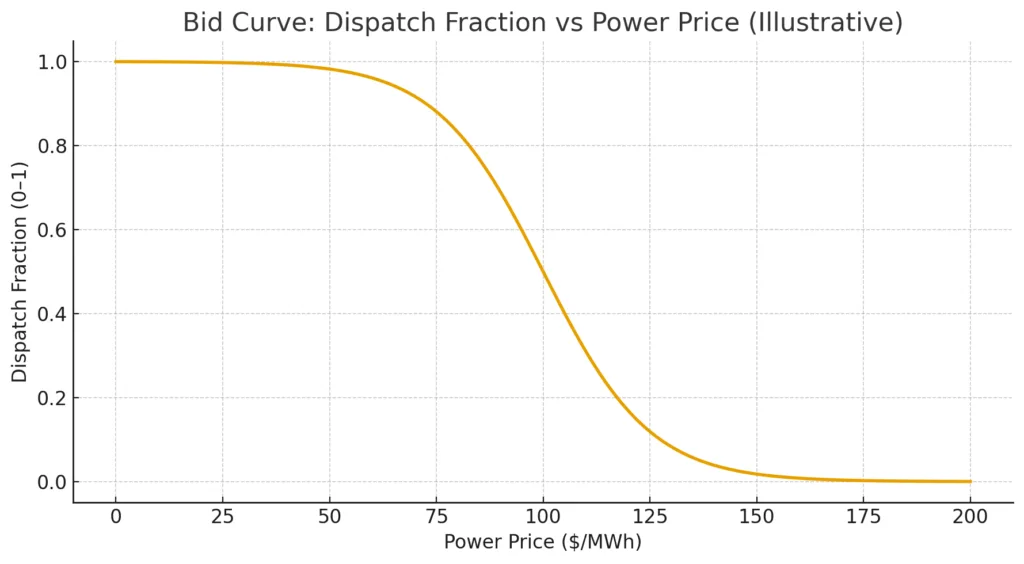

Energy arbitrage starts with structuring. Rather than a single flat tranche, a miner acquires a bundle: a solid block in the day-ahead market to secure a minimum hash strategy; a variable portion linked to real-time prices to seize lows; and a curtailment deal that compensates for reducing load during peak times. The operating system functions as a bid curve. Every hour, the controller evaluates the estimated “hash revenue per megawatt” against the total marginal cost of dispatch at that location, factoring in imbalance fees, demand costs, and the worth of missed curtailment credits. If the anticipated hash margin per megawatt dips under the curtail price, the controller decreases power or limits firmware; if it exceeds the firm block plus a spread, the controller increases to nameplate and, if feasible, overclocks within thermal constraints. In reality, this appears as a facility operating at 30–40% of nameplate capacity during late afternoon peaks, increasing to 100% after the evening ramp when renewable sources stabilize, and idling during shoulder hours. The miner profits in two ways: first by hashing during periods of low electricity costs, and second by selling energy back to the grid when electricity prices are high.

Behind-the-meter approaches follow the same reasoning. A miner located at a wind or solar facility utilizes the otherwise curtailed surplus of production, stabilizing merchant revenue for the asset owner and reducing its own average expenses. Surplus energy that would otherwise be wasted at negative prices turns into productive hash. Gas-to-power initiatives involving stranded or flared gas operate in a similar manner: the miner transforms a liability, methane that would otherwise be burned or released, into controllable electricity. The economics are not solely green; they are also local. By sidestepping pipeline limitations and midstream fees, the generator offers energy at a competitive rate that can significantly surpass grid retail prices. In both scenarios, the actual output of the miner is adaptable. The fleet needs to handle varying voltage and frequency, operate efficiently at partial loads, and withstand starts and stops without increased wear.

Thermal engineering represents the counterpart of arbitrage. Immersion, heat-recovery systems, and power-limiting software all convert temperature into money. In warm climates, the limiting factor is frequently the cooling system rather than the transformer; reducing chips to a lower joules-per-terahash level during peak temperatures can enhance effective uptime while extending silicon lifespan. In areas with district heating or industrial off-take, the monetization of waste heat alters the unit economics once more. The facility markets megawatt-hours twofold: once as computation and again as thermal energy, leading to a corresponding shift in cost allocation. The miner’s role isn’t to push for an additional percent of overclock but to optimize overall profit by balancing compute and heat according to hourly weather and pricing conditions.

Since volatility has both positive and negative impacts, hedging is essential. Power desks now offer shaped forwards, heat-rate options, and basis swaps that settle at designated nodes. A miner can secure the risky afternoon peak in July while utilizing spring shoulder months when renewable surplus is expected. Capacity rights are beneficial when transmission congestion is the cause: they provide compensation when the local node differs from the hub. Telemetry and automated bids in ancillary markets can help manage demand charges and imbalance fees. What was once a painful penalty for offline tripping has transformed into an arranged involvement in non-spin reserve, with telemetry verifying response times that compete with batteries. The facility receives a continuous payment just by agreeing to be the initial industrial load that vanishes when frequency fluctuates.

Everything relies on data. A skilled energy team processes weather predictions, renewable generation profiles, outage plans, and forward curves, then communicates an hourly dispatch strategy to the farm controller. The model requires three sub-modules: a predictive “hashprice” curve that translates BTC prices, fees, and anticipated difficulty into dollars per terahash; a nodal cost curve that calculates real-time power usage by hour with uncertainty bands; and a machine-level efficiency map illustrating how each ASIC reacts to ambient temperature and power limitations. The goal of the objective function is not theoretical profit; instead, it focuses on bankable cash margin after fulfilling contractual obligations, accounting for degradation costs and curtailment credits. That is the figure that should influence the on/off and cap choices every five minutes.

Regulatory and interconnection factors remain significant. Interconnection queues, deliverability analyses, and environmental approvals can nullify the most optimal spreadsheet arbitrage. Locations situated within transmission pockets might experience curtailment rates that surpass expected limits; gas facilities could face air-permit restrictions that cap operating hours; and behind-the-meter agreements need to define ownership of renewable energy certificates and the distribution of carbon intensity. The key point is not to steer clear of complexity but to assess its value. The flexibility that renders Mining 2.0 lucrative is also the flexibility that necessitates explicit contracts and strict risk boundaries.

The image that arises is of a miner who functions as a power trader, a plant engineer, and a systems integrator. Affordable average power is no longer the guiding principle. Success is achieved through inexpensive marginal power during optimal hours, at appropriate nodes, and within suitable thermal constraints, along with the contractual and firmware adaptability to convert volatility into profit. Energy arbitrage isn’t a niche; it serves as the engine that finances the entire strategy, ranging from hardware upgrades to derivatives hedging. When executed correctly, it decreases the variability of cash flows while simultaneously raising exposure to short-term price signals that many industrial loads cannot or choose not to respond to. That is the architectural advantage.

ASIC market microstructure and fleet optimization

The second component of Mining Economics 2.0 is the marketplace for computational resources. In Mining 1.0, the ASIC cycle resembled a neat staircase: every new generation brought a fresh joules-per-terahash milestone, early adopters reaped the excess, and the rest of the market slowly aligned. That image overlooked the microstructure that truly determines the price of hashpower: wafer distribution and yield fluctuations, foundry wait times, vendor cash flow, the second-hand rig market, and the variability within each batch of machines. A miner that views a fleet as one efficiency figure will miss out financially in two ways: by paying too much for new capacity and by not utilizing existing capacity enough.

Begin at the beginning of the supply chain. ASIC manufacturers accept prices set by foundries that distribute advanced wafers to numerous profitable customers. When demand for GPUs is high or mobile flagship models update, wafer costs and delivery schedules affect the mining setup. Vendors reply with advance order timelines, non-reimbursable deposits, and performance categories. The dispute involves more than just unit pricing; it concerns the reliability of delivery and the statistical quality of the chips. Two miners paying the identical listed price may acquire significantly different fleets if one has an advantage on the binning curve. In reality, binning indicates that certain machines will achieve the advertised efficiency easily, while others need increased voltage to maintain the desired hash rates. The disparity manifests as a genuine distribution of joules-per-terahash among seemingly identical rigs.

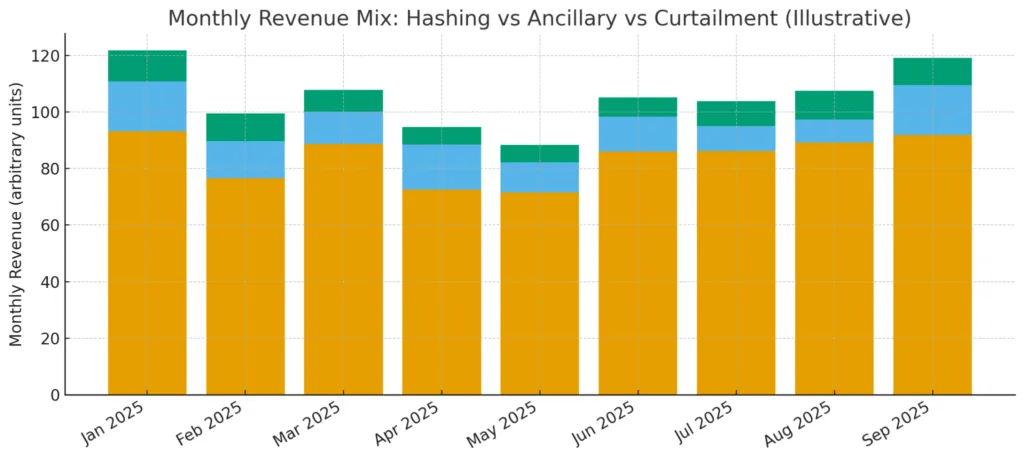

That spread is the reason the appropriate unit of account is not the brochure figure but rather effective efficiency after controls and context. Immersion will alter the curve and make it more compact; warm, dry air will move it in the opposite direction. Tuning firmware is equally important. Autotuners that seek per-chip frequency and voltage can achieve 5–10% efficiency improvements in the optimal section of the distribution, but they may also lead to the failure of marginal chips if thermal headroom is limited. The economic goal is not to increase terahash at all costs; it is to optimize dollars per megawatt while considering failure risk, downtime, and the power price in the upcoming hour. A plant capable of instant power-cap can position machines at their optimal efficiency during costly hours and move them up the curve when electricity is inexpensive, thereby effectively establishing a merit order within the fleet.

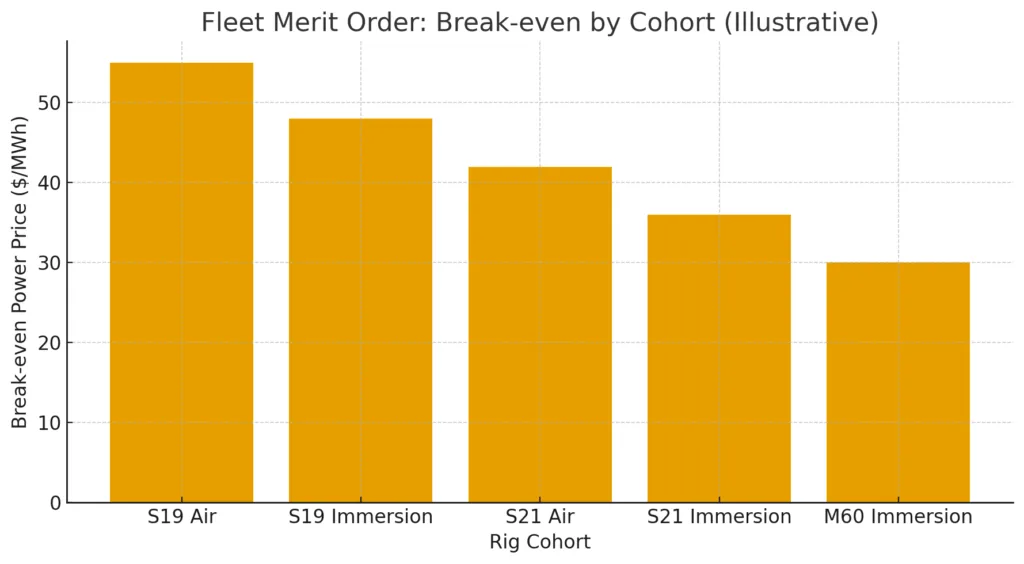

The merit order is an arrangement of rigs based on their break-even power costs. Every cohort based on model, age, cooling, and tuning possesses a power limit that necessitates curtailment beyond it. That threshold is merely the proportion of hash revenue per terahash to joules-per-terahash, modified for overhead and degradation. Overhead is frequently undervalued. Transformers, switchgear, pumps, fans, and parasitic loads use actual megawatts, transforming an appealing brochure efficiency into a poorer overall facility efficiency. Mining 2.0 addresses this transition by shifting from J/TH to J/TH at the meter and by monitoring “hashes per megawatt of site consumption” instead of hashes per megawatt of PSU rated capacity. The important KPI is not just W/TH, but TH/s per MW of overall facility draw at a specific ambient and setpoint.

The second area where microstructure is beneficial is the used-rig market. During downturns, desperate operators inundate secondary markets with hardware that is marked down for the incorrect reason: their power agreement, not the equipment. A buyer with flexibility regarding power can align that hardware with their specific cost curve and identify positive carry while the seller perceives a stalemate. On the other hand, in upcycles, lead times for new builds increase and the prices for used rigs rise; the dilemma is whether to invest in an expensive immediate installation or to opt for a less expensive future slot with guaranteed delivery. The correct response relies on the progression of difficulty and the configuration of your power. If you can exert yourself over the next ninety days while hashprice is high, investing in quick delivery can excel. If your edge is a shoulder season in spring with negative pricing and your site is still undergoing commissioning, utilizing forward slots with vendor financing might be more advantageous.

Failure rates and spare parts policies must be regarded as a financial choice, rather than an afterthought in maintenance. Failure rates at the board level depend on thermal cycles, dust exposure, voltage stress, and quality of workmanship. Immersion lowers particulate risk and temperature fluctuations but brings its own challenges: leaks, fluid deterioration, and chemical interactions that may corrode metals over extended periods. A spare parts strategy that maintains an active shadow inventory of hashboards and PSUs enables a plant to navigate failures without sacrificing dispatch flexibility. The expense of holding spare parts is significant, but the lost opportunity of not utilizing the lowest-cost hours due to a delayed bench is also substantial. In reality, a healthy spare parts ratio typically falls between 3–7% for aggressive operators, with increased buffers in harsh climates or single-line setups where a malfunctioning transformer strand takes an entire row offline.

Procurement agreements are changing to align with these circumstances. Vendors currently provide performance-based pricing, where a set of machines is priced according to a reference efficiency and settlements are determined by the actual distribution delivered. Some combine warranty extensions, immersion-ready heatsinks, and curated firmware into a complete solution that costs more but reduces integration risk. Revenue-sharing agreements linked to pool payouts are coming back, especially for underfunded sites that can provide quick energization. For purchasers, the essential point is to steer clear of paying for optionality more than once. If you provide the vendor with a revenue share that includes volatility, you ought to seek firmer delivery commitments, stricter bins, or service-level agreements regarding replacement turnaround times.

Funding is the third component. Loan products supported by machines and structured leasing agreements have evolved since the previous cycle. Lenders that faced losses from mark-to-market covenants related to Bitcoin pricing now evaluate against a mixed collateral portfolio: machines appraised using a cautious secondary-market curve, power agreements with transfer rights, and occasionally a cash reserve supported by daily pool distributions. The least expensive capital still carries the toughest covenants. A miner with genuinely adaptable power should advocate for agreements that acknowledge curtailment income and ancillary involvement as components of EBITDA; otherwise, the contract will disadvantage the very actions that generate value in fluctuating power markets.

Everything mentioned leads to a straightforward yet effective approach: deploy the fleet like an energy facility. Construct a supply stack of rigs through optimal efficiency, superimpose the hourly power cost curve, and establish a dynamic cut-line that adjusts with changing weather, difficulty, and fees. Within immersion, take into account two operating points for each cohort: a high-efficiency point during costly hours and a high-throughput point during less expensive hours, enabling the controller to adjust without direct assistance. Monitor degradation directly by recording voltage, temperature, and time at intervals; consider accelerated wear as a sales expense during hours of overclocking. When the expense of wear is evaluated, the controller will likely avoid pursuing marginal terahash during average power when those hashes are not profitable on a total-cost basis.

The miners who absorb this microstructure appear distinct. Their purchasing is organized into segments with flexibility on delivery. Their locations are built for quick ramp-up and secure idle, not solely for 100% uptime. Their maintenance stations operate like pit teams, and their firmware regulations are reviewed like financial records. Crucially, their P&L divides “Levelized Cost of Hash” similarly to how a utility monitors levelized cost of energy: in dollars per petahash generated throughout the machine’s economic lifespan, factoring in energy, overhead, maintenance, and depreciation. Using that metric, the decision between a discounted used fleet powered by inexpensive spring energy and a top-tier new fleet operating on stable power becomes non-ideological. It transforms into a spreadsheet that, in Mining Economics 2.0, the top operators are now creating and utilizing.

Derivatives and the integrated hedge

Mining Economics 2.0 views the miner as an active risk manager rather than a passive price-taker, with the ability to break down their P&L into exposures that are hedgeable in most situations. The main revenue generator, hashprice, is a composite: it increases alongside bitcoin’s spot price, decreases when network difficulty rises, and adjusts in response to transaction fees. Regarding costs, the most significant variable is power, which comes in forms that can be hedged in various ways across hours, months, and locations. The purpose of the derivative stack is to transform that chaotic collection into a risk book where the deltas are clear, quantified, and protected by contract instead of chance.

At the pinnacle of the stack are bitcoin derivatives. Basic schedules that offer a portion of daily output for sale at market stabilize cash flow and mitigate volatility, yet the post-halving environment favors increased accuracy. Collars funded with covered calls create a safety net for operating cash while allowing for potential gains when fees increase. Calendar spreads and perpetual basis trades transform inventory into cash while retaining some directional optionality, an advantageous strategy when treasury policy necessitates maintaining a core BTC balance across cycles. The error in this situation is to only hedge the price while neglecting difficulty; the miner later finds that the effective hashprice still declined because the network’s overall computing power surpassed the hedge.

Risk associated with difficulty is becoming more tradable. Hashrate- or difficulty-based forwards and swaps enable an operator to capitalize on production using a reference index for a fixed duration. These tools provide returns when network difficulty increases and tightens margins, exactly when defense is required. Structures can be combined with price hedges to form synthetic revenue floors that correspond to both BTC and difficulty, resembling the behavior of actual cash flow more closely. Liquidity in BTC options is more limited, so sizing must account for capacity constraints and collateral regulations; however, even slight adjustments can stabilize the future cash plan.

Power risk aligns well with the terminology used by commodity desks. Shaped forwards set the price for the riskiest hours, heat-rate options provide protection during severe shortages when gas determines the marginal cost, and node-hub basis swaps alleviate the impact of congestion when local node prices differ from system prices. When the location operates behind the meter, the hedge frequently shifts to the generator’s income: a merchant solar or wind collaborator might hedge their own production with the miner’s offtake included as a secured sink in times of oversupply. When permitted, participation in ancillary markets represents a separate derivative exposure: the duty to reduce load upon request acts as a short option on the frequency of the grid, with premiums compensated through monthly capacity or performance payments.

The combined hedge arises when these layers are aligned with a unified goal: maintaining a steady cash margin over the upcoming one to four quarters while retaining the strategic potential that validates the business. Essentially, this involves correlating the book with a limited collection of greeks: responsiveness to BTC price, to difficulty, to the nodal power curve, and to fees. A dispatchable fleet can lower those greeks instantly by reducing or capping power when the margin drops below the hedge floor, transforming operational flexibility into a financial tool. Governance is just as important as mathematics. Risk limits must restrict the proportion of expected output that is pre-sold, establish minimum liquidity for margin calls, and avoid redundant hedges that offset each other. The ultimate test is counterfactual: if bitcoin fell, difficulty increased, and the node experienced a month of delays, would the cash strategy still meet payroll, debt obligations, and capital expenditures? If the response is affirmative without any exaggeration, the derivative stack is functioning.

Treasury, financing, and the capital stack

A miner that views treasury as a trading floor will stray from its purpose; a miner that considers treasury as a mere accounting detail will lose flexibility. The central route is guided by policy and systematic. Self-mined coins are categorized by their purpose: a working-capital segment transitions to fiat on a continuous schedule linked to operating expenses; a reserve segment finances coupons, leases, and covenant upkeep; and a strategic segment is regulated by draw-down conditions and pre-established hedging agreements. Basis trades can generate revenue from the reserve without complete liquidation, but the policy needs to specify when basis may be utilized and when it needs to be terminated to release collateral.

The financing options are more extensive than before. The vendor pre-pays and shares revenue, trading gross margin for reliable delivery and reduced initial cash outlay. Loans supported by machines are progressively secured against practical secondary-market curves and assignable power contracts, instead of pro-forma BTC values. Site-level project finance arrangements can isolate risk and draw in more affordable capital when power agreements and interconnection rights are robust. Regardless of the combination, covenants must acknowledge curtailment and ancillary revenues as EBITDA; failure to do so could lead to breaches of ratios in unpredictable months due to the behaviors that generate value. Liquidity buffers warrant the same consideration as megawatts; having a quarter of fixed operating expenses in unencumbered cash is more cost-effective than the equity you would liquidate during a drawdown.

Risk, regulation, and accounting frictions

Regulatory risk now focuses on how mining is integrated rather than whether it is permitted. Interconnection analyses, air quality permits, noise regulations, and demand-response program guidelines can eliminate projected margins if taken lightly. Behind-the-meter agreements need to determine ownership of renewable energy credits, the method for measuring carbon intensity, and if methane mitigation credits can be claimed and sold without duplication. Cyber risk has become operational risk; telemetry generating additional revenue also broadens the attack surface, thus network segmentation and incident drills must be regarded as production safeguards rather than mere paperwork.

Accounting rules can warp incentives. Under some regimes, digital assets still face asymmetric impairment, so inventory carried for treasury purposes may create P&L noise that is orthogonal to cash. Derivative accounting can drag operational hedges into fair-value volatility if designations are sloppy. Power-related credits, curtailment payments, and environmental attributes need consistent policies that tie recognition to delivery and verification. None of these frictions are existential, but each can turn a well-engineered plant into a lumpy financial reporter if ignored.

Metrics, operating system, and the miner’s edge

The system that unifies Mining Economics 2.0 is a field of assessment that reflects a power generator rather than a speculative investment. At the hardware level, the primary metric is the levelized cost of hash, indicated as dollars per petahash generated throughout a machine’s economic lifespan, incorporating energy, parasitics, cooling, spares, and degradation. At the site level, the real-time dashboard should highlight effectiveness at the meter instead of promotional figures, hours utilized at the fleet’s best efficiency point instead of total uptime, and cash margin per megawatt instead of non-specific hashrate. In terms of market considerations, the miner must monitor the percentage of the upcoming ninety days of output that is protected by instrument and exposure, the variability of daily cash margin based on existing hedges, and the actual capture of nodal troughs and curtailment premiums in comparison to the strategy.

Cadence transforms these figures into something valuable. A weekly meeting among energy, fleet, and treasury integrates the dispatch curve, repair bench, and hedge book into a single plan. A monthly risk assessment evaluates liquidity in relation to adverse scenarios and resolves overlapping positions. A quarterly capital committee reassesses projects based on a fluctuating difficulty and power forecast, ensuring that capital expenditures target the most favorable projected dollars per megawatt instead of just the most impressive specifications. When this rhythm is maintained, the miner’s advantage accumulates subtly: lower marginal energy costs as the grid has confidence in the site’s performance; reduced capital expenses due to covenants aligning with actual circumstances; and cheaper hashes because the fleet operates at its optimal point instead of an idealistic 100% output. In this regard, Mining Economics 2.0 focuses less on price speculation and more on the skill of transforming volatility among three markets energy, compute, and capital into consistent cash flow.